This story was originally published in the June 2025 edition of the ECFS Reporter.

At ECFS, research is a critical academic discipline deeply rooted in our educational philosophy. Our teachers support students as they learn to find and evaluate information, synthesize ideas, and communicate findings, creating a foundation for thoughtful and informed problem-solving in academic and real-life contexts. We asked faculty members across all four divisions to share a bit about the projects, units, and activities that promote intellectual curiosity and most effectively cultivate strong, inquiry-driven research skills.

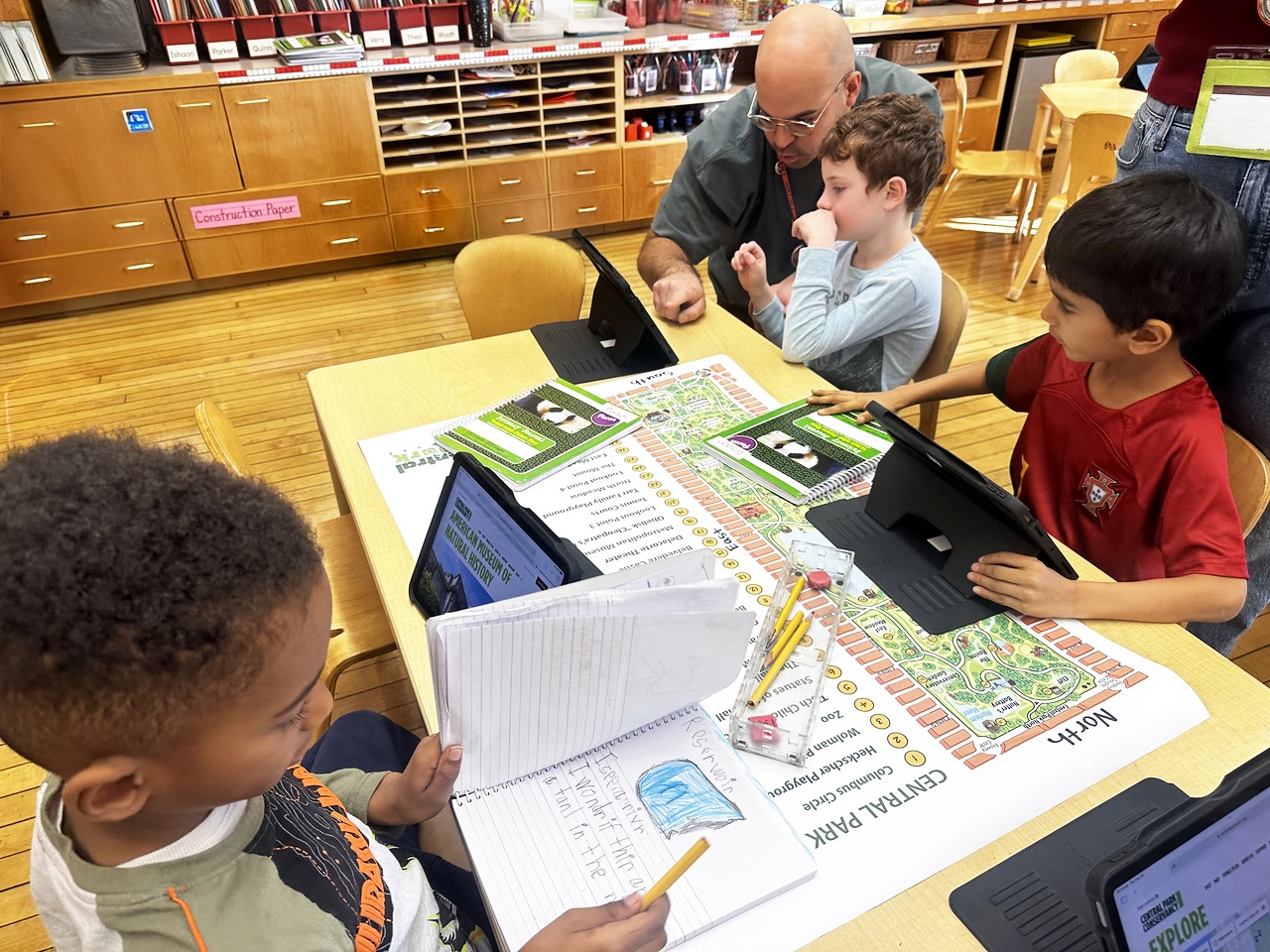

“The 1st Grade Central Park study is a wonderful opportunity for learners to engage in experiential and meaningful research grounded in their interests. Given the park’s proximity to our School, they begin the study by leveraging their personal experiences to define its attributes and features. Together, we generate questions and find answers using map skills, readings, and interactive maps filled with fascinating facts. Students practice note-taking and document their learning in journals, and to connect this research with real-life experiences, our research teams embark on field trips to the park.

The project truly comes to life when the concept of three-dimensional model-making is introduced as an alternative way to explore new learning. The 1st Graders join design teams and take turns working in the block area to build various landmarks in the park. Each year, the model evolves to reflect students’ interests. Some years, teams focus on populating the map with trees, while in other years, playgrounds take center stage. It’s always very exciting to see how student interest drives the study. Beyond sparking curiosity, the study strengthens research, observation, and documentation skills — critical tools they will continue to build on in future grades.”

— José Ramos

1st Grade Head Teacher, Ethical Culture

“The 6th Grade unit on the Delano California Grape Strike touches many tenets of ethical thinking, learning, and practice. We explore the questions that arise and connect us to our theme of building a healthy community. After watching two films that share different experiences of the actions leading to and sustaining the grape strike, students prepare for and participate in a seminar. On seminar day, each student has a packet containing photographs, quotes, personal reflections, and speeches that summarize the research we have assembled throughout the unit. Using their observations, interpretations, and best thinking, they explore the role of activists in building a healthy, more just community. The seminar concludes as everyone shares a closing statement about what they learned from their investigation and one another. Before the seminar, students ask questions, test their knowledge, write in their journals, explore interactive maps, draw, learn songs, and engage in thoughtful questions with one another.

This integrated approach strengthens critical thinking and helps students connect historical activism to the challenges of today. The atmosphere buzzes like a well-tended garden, which tracks well with the word seminar, whose root is the Latin word for seed.”

— Abena Koomson-Davis

Ethics Department Chair, Fieldston Middle

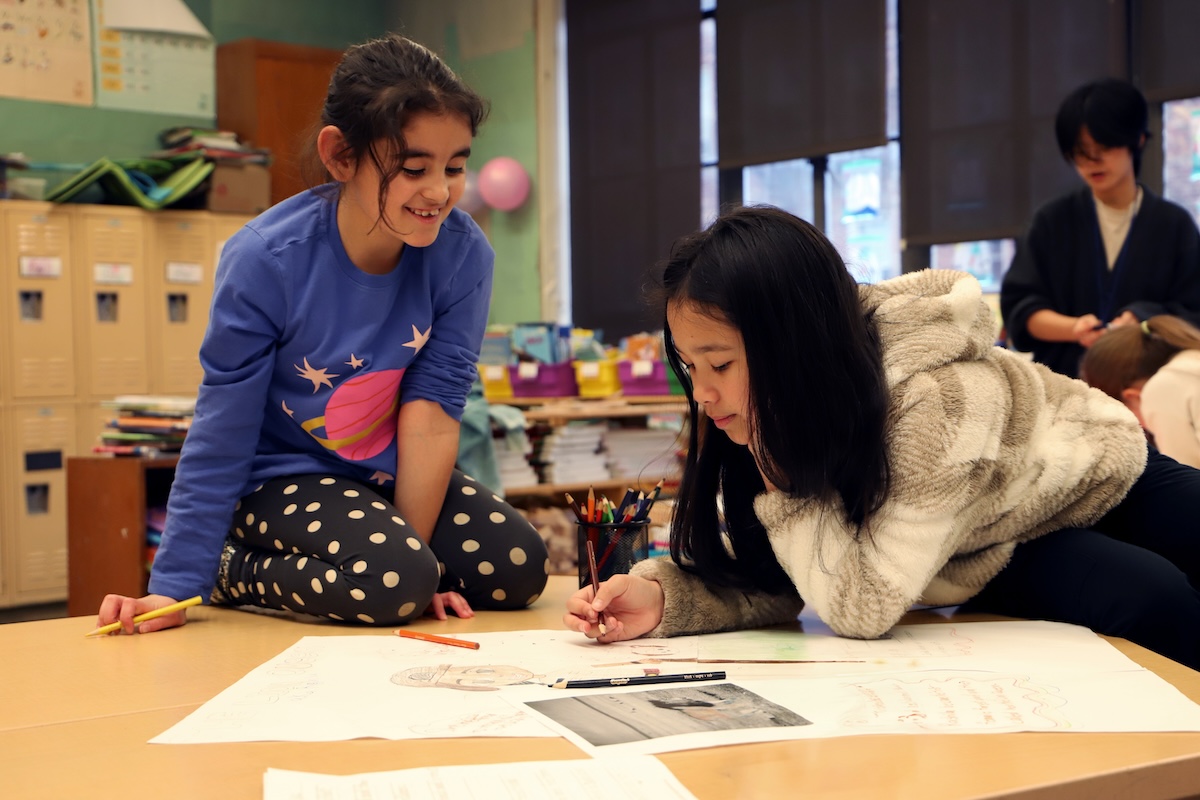

“The Harlem Renaissance ’zine project combines research, collage techniques based on Romare Bearden’s work, poetry the children have written about home, and illustrations highlighting a key figure from the Harlem Renaissance. ’Zines are made by hand, following a layout and design process. The ’zine project captures the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance: taking risks to create art for oneself and community with a ‘do-it-yourself’ approach that relies on community rather than hierarchical institutional systems. Students are especially engaged because they take ownership of both the research and the creative process, making their learning hands-on and meaningful.”

— Rebecca Butler

5th Grade Head Teacher, Fieldston Lower

“‘The Machine Stops,’ by E.M. Forster, is a thought-provoking novel first published in 1909 that imagines a future eerily like our present day, in which devices absorb our attention while we remain physically remote from each other, compulsively entertaining ourselves with various ‘social’ media while at the same time being peculiarly isolated, as if in our own private bubble. In reading the book, students can consider how this fictional world does and does not resemble their own experiences with technology.

The goals of this project are empowering students to pay attention to what seems to be underappreciated at Fieldston or in Middle School more generally and, also, imagining how students themselves as changemakers might improve our school community in specific ways.”

— Brad Fraver

English Teacher, Fieldston Middle

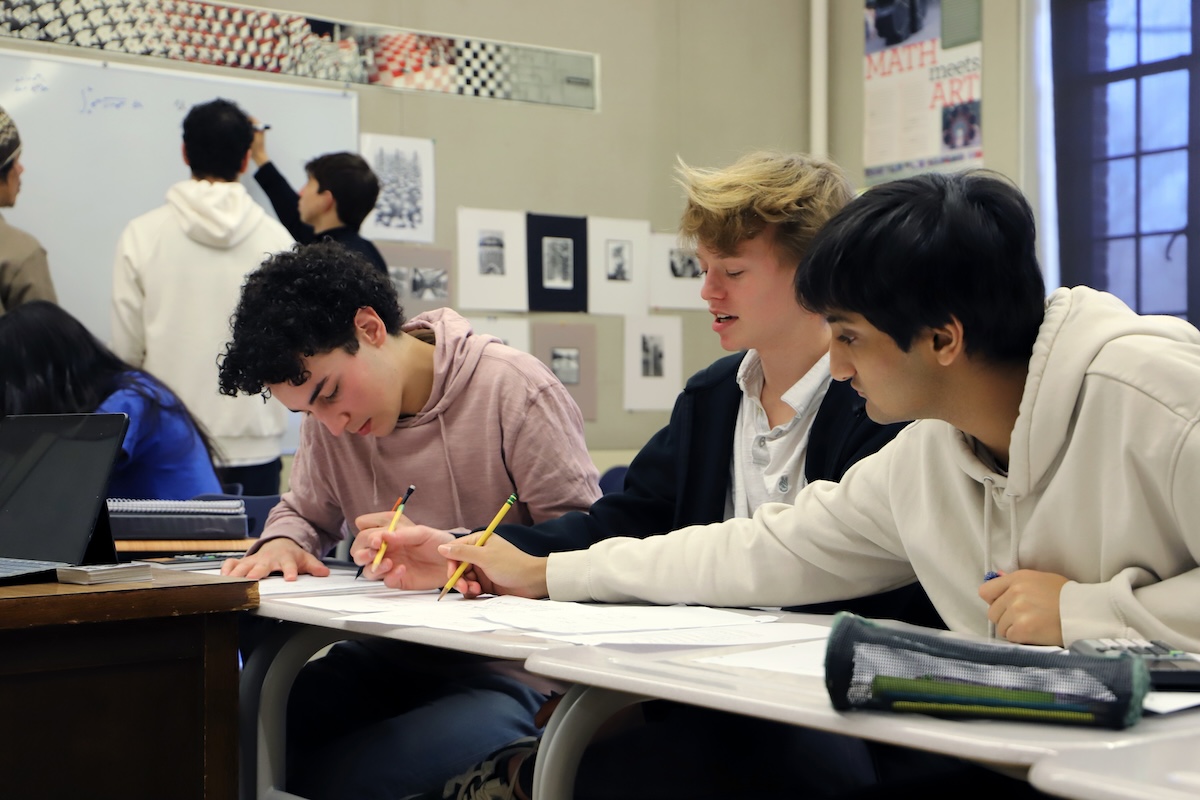

The 11th Grade AT Calculus 1 class’s unit on differential equations challenges students to recognize how differential equations can be used to model and understand phenomena in other disciplines, bridging the gap between abstract mathematics and real-world applications. Students work in groups of two or three and can choose which application to research in depth. In the past, their choices included the SIR model used to model the spread of infectious diseases, modeling the effects of air resistance on falling objects, and peak oil and the consumption of natural resources. One of the key experiential learning takeaways of modeling is asking, ‘Can we make predictions from this model? Does it correspond to actual data? What can it teach us about this phenomenon?’

Students complete a series of scaffolded questions that help them understand how mathematics connects to each topic. We also ask them to do background research to provide more context and, in the end, produce a written paper and give a short share-out to the class. The project relies on students being savvy and relying on rigorous research skills they’ve already developed in other classes.

— Stephen Chu

Math Department Chair, Fieldston Upper

“Our changemaker unit is a yearlong study of people who make the world a better place. As teachers, we introduce people from diverse backgrounds who impact their local community and beyond. We learn about adults, young people, and people from the past, incorporating historical figures who have significantly changed how we live in the world today. However, we also learn about inspiring people who are less familiar to students, bringing relevance to an unheard name that may not be so commonly spoken or someone not too distant from their community. Using real-life stories of those connected to social justice, environmental activism, and inclusivity, we hope that students see themselves as citizens of the world who can also forge a life of service and positive impact. To bookend our learning about changemakers, we scout community service projects every year so students can take action and be a voice forour Fieldston community well into the future.”

— Melanie Corcino and Monique Astengo-Rosen

2nd Grade Head Teachers, Fieldston Lower

“The evolution of students’ relationship to places familiar and unfamiliar in our city, as well as their ability to synthesize multiple physical and conceptual vantage points, culminates in our policy memos. In this group project, a semester’s worth of new perspectives — shaped through classroom study and hands-on fieldwork, including volunteering in community gardens and other local initiatives — is channeled into an in-depth exploration of a single policy subject and its implications for a specific neighborhood. The policy papers, which students spend several weeks immersing themselves in a single policy topic of their choice, are where we see the rigorous transformation that City Semester promises: from a clear moral vision to civic engagement. In Felix Adler’s famous words, the project ensures that students are ‘competent to change their environment to greater conformity with moral ideals.’”

— Roy Blumenfeld

City Semester Director, Fieldston Upper

“One of my favorite classroom projects is our research unit on historical landmarks, such as Machu Picchu and the Great Pyramids of Giza. The students prepare for research through a series of lessons on nonfiction, including practicing self-monitoring strategies such as chunking, annotating, and exploring text features. Working in small groups, they gather and organize key facts on their chosen landmark’s history, appearance, location, and significance using differentiated texts, videos, and other visual tools. Once they have collected this information, they are challenged to transform their research into structured, cohesive paragraphs. I love how seamlessly this experiential process strengthens their critical thinking skills while also reinforcing the value of revision. Later in the year, the project naturally transitions into independent research on prominent Indigenous figures, empowering them to apply their learning with greater autonomy.”

— Ty Yueng

3rd Grade Head Teacher, Ethical Culture